Close school doors through February: going remote or going outdoors are the only two responsible options

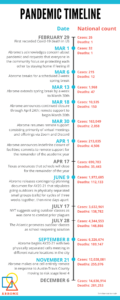

In early March with an eye on the quickly rising Covid-19 case count and death toll in northern Italy; educators, administrators, and politicians were debating what schools should do to help stem the inevitable tide of infections coming to the United States; as well as to protect students, teachers, and staff. Abrome, along with many others, recognized at the time that the risk of bringing people together was too great given the many unknowns about the virus. As such, Abrome ended up canceling in-person meetings for the remainder of the 2019-2020 academic year, and schools statewide soon followed suit.

As summer neared, a combination of business interests, political interests, and institutional pressures were weighed against public health concerns in the debate over how and when to reopen schools. Abrome approached the issue with a focus on allowing Learners and Facilitators to more safely come together while also contributing to the societal effort to stop the spread of the disease.

As observational studies and experiments improved the understanding of how the disease impacted people and how it spread, several factors became overwhelmingly clear. First, it was a disease that was transmitted via viral particles—primarily through droplets and aerosols. Second, one must be exposed to a critical mass of viral particles (the viral inoculum) to become infected. Third, because of the prior two factors, universal masking significantly reduced the likelihood of transmission. Fourth, largely influenced by the first two factors, congregating indoors with others greatly increased the likelihood of transmission.

With these factors in mind, Abrome was able to avoid being distracted by the talk of rotating schedules, hybrid schooling, desks spaced six-feet apart, and plexiglass dividers that kept the idea of schooling in a facility at its core. By focusing on the factors driving the spread, it quickly became clear that the only practical way to bring Learners together without putting people inside and outside of the Abrome community at risk from Covid-19 was to leave the schoolhouse behind—meeting entirely outdoors, masked up, in physically distant, small groups. Abrome released it’s pandemic plan on June 9th and spent the rest of the summer preparing and training to be outdoors in the elements, and communicating with families and Learners so they understood what practicing freedom outside would look like. It was not easy, although it would prove easier and safer than trying to keep kids masked up and 6-feet apart in classrooms while repeatedly sanitizing surfaces.

Six months later, the nation is rushing headfirst into the worst stage of the pandemic. According to The Covid Tracking Project, as of Monday, December 7th, 102,148 people were hospitalized with Covid-19, meaning there are currently 70% more people hospitalized with Covid-19 than there were at the peaks of the first (April) or second (July) waves of the pandemic. The 7-day average number of new cases is 196,882, up 16% from two weeks ago. And the 7-day average number of deaths from Covid-19 is 2,204, up nearly 47% from two weeks ago, surpassing the worst week from the first wave of the pandemic. While recent vaccine developments provide hopeful pathways to ending the pandemic, the next few months will be the worst of it. And the actions that society collectively chooses to take will determine the scale of suffering and death that will make up this stage of the pandemic.

The most meaningful choices that society can make to minimize harm this winter are fairly straightforward. On an individual level, wearing masks and avoiding unnecessary interactions with those outside one’s household or dedicated pod is the first step. With the exception of those forced to work in settings with other people to survive, if one needs to interact with those outside their household or dedicated pod, they should only do so outdoors (in small numbers, distanced, and masked up). They should not eat out, go to a bar, exercise in a gym, go to a spa or salon, or attend any event with large numbers of people (e.g., religious services, sporting events).

However, it seems that relying on individuals to commit to the aforementioned practices in order to stop the spread of infections seems unattainable at the moment. Institutions must also do their part to limit the harm. Institutions should make it easier for individuals to make good choices and they should make it impossible for people to make choices that needlessly put everyone else at risk. For example, restaurants should eliminate indoor dining, while bars, gyms, spas, and salons should close their doors for the winter. Any organization that relies on large groups of attendees should cancel all events until spring. And schools should either go remote or go outdoors.

At this stage in the pandemic, society should be rallying to lock schoolhouse doors to prevent students, teachers, and staff from coming together indoors. Not because schools are the main driver of the pandemic, but because they contribute to the growth of an out of control pandemic. However, due to a misunderstanding of how the disease spreads and false notions about the immunity of children, the demands to put students back in classrooms continue to pour out. Regrettably, the reopen schools now cry has been given an outsized platform by the media, taking up valuable space that crowds out far more sensible arguments, despite the worsening trajectory of the pandemic over the past couple of months.

Many people generally understand that to combat the spread of Covid-19 that masking is good, congregating indoors is bad, and that interacting only with those who live in the same household is ideal. They have probably heard of R0 or Rt, and know that reducing the average number of people infected by a diseased person can help bend or flatten the curve. But far fewer know about k, the measure of a disease’s dispersion.

For Covid-19, the value of k is closer to zero than it is to one, meaning that a minority of those infected lead to a majority of new infections, that infections tend to happen in clusters, and that superspreading events are a key driver of the propagation of the disease. It is estimated that “as few as 10 to 20 percent of infected people may be responsible for as much as 80 to 90 percent of transmission, and that many people barely transmit it.” (That quote comes from a great primer on k written by Zeynep Tufekci for The Atlantic.) Unfortunately, we do not know who is likely to be in the minority of people who are responsible for the majority of infections, but each new infection creates a potential pathway to a future cluster or superspreader event. For this reason, it is necessary to take actions that limit the possibility of superspreader events from taking place.

A highly infectious person alone is not sufficient for a cluster or superspreader event to take place. Other factors help create the conditions for such events. The most obvious is the presence of other people available for infection. The more, the less merry. By limiting the number of people who congregate, the organizers of spaces can put a cap on the scale of a potential superspreader. Being indoors is another, as the odds of transmitting the disease in a closed environment are nearly 19 times greater than in open-air environments. While better ventilation systems can help reduce the buildup of viral particles, being outdoors is still the surest bet against it. The longer the amount of time that people spend together indoors, the more forcefully that people are emitting particles into the air (e.g., exercising, singing, speaking loudly), and an absence of mask wearing also contribute to the likelihood of a cluster or superspreader event occurring. These factors help explain why households are one of the most common cluster sites.

We also now know that it is likely that the majority of infections are spread by people who have no symptoms (pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic). This means that we cannot rely on effective screening mechanisms or people voluntarily staying at home when they feel ill to stop the majority of new infections.

Schools bring the worst of all of the aforementioned factors of spread together in one setting. They bring large numbers of students, teachers, and staff together; indoors; for up to seven hours a day (not including extracurricular activities); where teachers and students are speaking loudly, singing, or running around. And some schools are not even requiring universal masking when indoors or around others. Even if the schools are running at only 30% capacity, and the students are stuck at spaced out desks doing personalized learning all day, the schools are still potential cluster or superspreader sites as they still meet most of the aforementioned factors, and they allow for the creation of new pathways to future events.

Sadly, the reopen schools now campaign continues to get pushed by parents, politicians, business, and the media. The endless cries about the harm that is being done to kids by being out of school has even convinced many public health officials to carve out schools as the one place that should continue bringing large numbers of people together indoors during the pandemic, even though schools are potential superspreader sites. (It should be noted that public health officials usually add the caveat that sufficient safety measures should be in place, which is not happening in American schools.)

Perhaps the most common point in favor of reopening schools is that kids are less likely to get seriously ill or die than the rest of the population. While that is true, what that point misses is that kids still get infected in school, and they still take the disease home where they can infect family members. Those family members can become seriously ill and die, and once infected family members can continue to spread it to others in the workplace or elsewhere in the community. And each new infection creates a potential pathway to future mass infection events. That kids are less likely to get seriously ill or die also ignores that adults work in the schools with the kids. Teachers and staff are not less likely than the general population to suffer from the disease, and when people pound their fists about how kids are relatively immune they are erasing (in more ways than one) the adults who work in schools.

As to the point that the kids are suffering by being out of school, particularly poor students and students of color, it should be noted that kids will suffer far more from seeing family members suffer from illness or death, especially if they are the ones who brought the disease home from school. Finding out that their teacher has died is also pretty traumatic.

There are other shaky claims about the need to risk bringing students, teachers, and staff in schools during the most dangerous stage of the pandemic such as the students will “fall behind” (fall behind what, exactly?), or schools are where children get access to food, or schools are the only place where many children feel safe. These arguments tend to center a very negative view of children, as well as the quality of home life for poor students and students of color. And each one deserves an essay tearing down their position as an argument in support of poor, Black, or brown kids; even though in most cases those arguments are being made by members of more affluent, white communities who are demanding that their local schools reopen, not by Black or brown families who tend to understand that conventional schools have not historically centered the needs of their children.

So what should school boards, administrators, and leaders do, now, during this worst stage of the pandemic? From a public health perspective it should be vividly clear that they should not reopen schools. If schools are still open, they should close. There are only two viable options for schools at this moment in time: go remote, or go outdoors. And while going remote is not great for many kids, and from a conventional schooling perspective it is less than ideal because teachers have less control over kids’ bodies and minds during the day, it drastically cuts down the number of contacts each student (and teacher) has each day. But for those who argue that the kids need to be in class, and they need to have access to school services in the midst of the worst stage of the worst pandemic in a century, they should simply take the classroom outdoors. It is possible. It has been written about (sometimes even in the same publications that argue that schools need to reopen). It has been done elsewhere. Abrome has done it. Of course it is easier when schools don’t feel the need to recreate their indoor classrooms outdoors. They could allow students to move freely during lessons; they could introduce a more self-initiated, self-guided curriculum; or they could even consider letting go of schooling during these difficult times and allow the children to practice freedom (with the support of teachers). But they should certainly limit the size of each cohort to no more than ten individuals, and they should not allow the cohorts to mix in any way.

It’s been a long nine months since the first recorded death of Covid-19 in the United States. In this country there has been an ideological struggle between those focused on collective action (e.g., masking, closing schools and bars) to slow down or stop the spread of the disease, and those focused on the right of individuals to not live in fear, which too often means engaging in risky activities that expose them (and others) to the disease. Disappointingly, we as a society were not able to come together and temporarily curtail our activities in a way that could have saved what will likely be hundreds of thousands of lives lost. But now, for the next few months, we can finally say enough is enough, and that we will do what it takes to get through this winter without escalating the death toll. And doing what it takes includes closing the school doors and either taking class outdoors, or going remote. And at some point, when community spread is too high, going remote will be the only option.